Features > Property News & Insights > Market updates

What’s needed to fix Australia’s housing crisis?

Image from Eliza Owen's LinkedIn Page

KEY POINTS

- A leading housing analyst says simply increasing dwelling approvals won’t fix Australia’s housing shortage

- Cotality’s Head of Research says with 219,000 homes under construction and another 30,000 approved but not yet started, the real issue is delivery bottlenecks

- Eliza Owen says without boosting construction capacity and efficiency, more approvals risk exacerbating delays, fuelling inflation, and worsening housing supply outcomes

One of Australia’s leading housing analysts says governments and the building industry need to focus on obstacles to the delivery of new housing, not speeding up approvals for new homes.

Cotality’s Head of Research for Australia, Eliza Owen, says that with 219,000 homes already under construction and completion times ballooning, the real bottlenecks lie in building, not planning reform.

The details

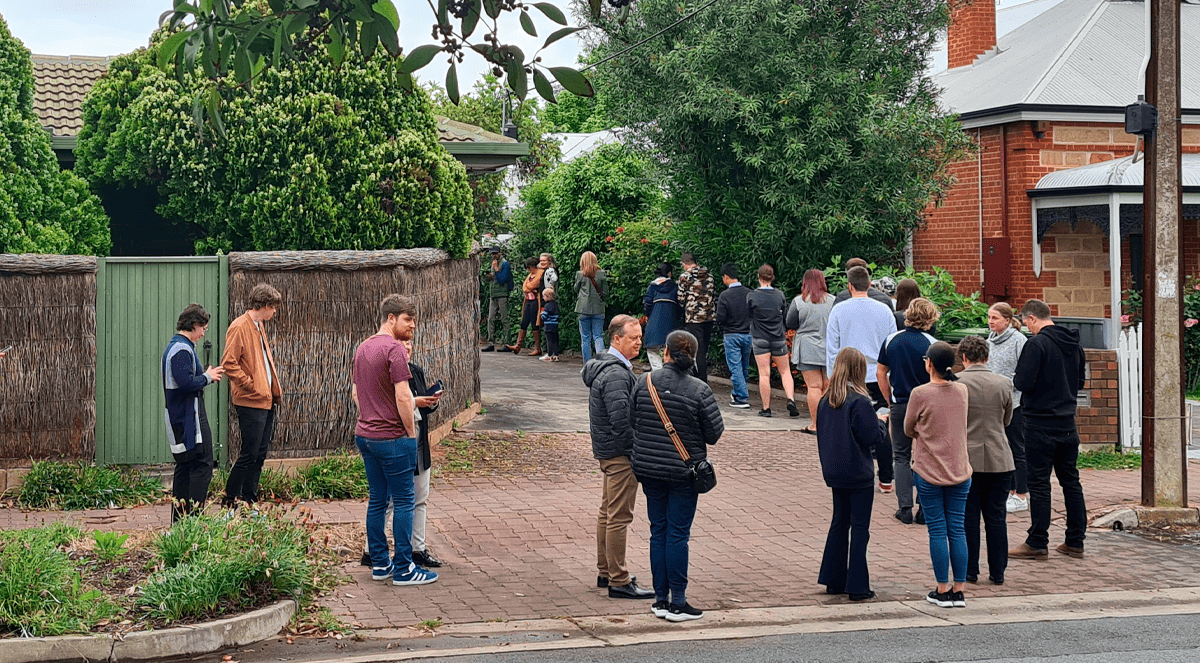

As governments across Australia scramble to solve the housing crisis, a deeper look at the nation’s construction pipeline suggests a complex and challenging road ahead.

While approval numbers are often held up as proof of progress, Cotality’s Eliza Owen says the reality on the ground is that too many dwellings are getting stuck in the pipeline — and not enough are getting built.

From the moment the Federal government unveiled its target of building 1.2 million new homes over five years in August 2023, industry insiders raised doubts about whether it was achievable.

“The core of the problem with any government target for new dwellings is that the government can’t influence many of the factors that determine demand and supply,” Ms Owen says.

While the Federal and state governments have tried to push through planning reforms and incentives, builders continue to face cost pressures, labour shortages, and stretched margins — all while grappling with a construction pipeline that’s already at capacity.

“Looking at the construction pipeline shows that policy change is urgently needed in the enablement of quality construction, rather than new dwelling approvals,” Owen says.

Lessons from the last boom

Australia has never built 1.2 million homes in five years, although build rates were much higher in the five years to 2019.

But conditions then were vastly different.

Ms Owen points out that the cash rate then averaged just 1.6%, compared to 4.18% since July 2024.

Almost half of all housing approvals were for units (46%) — a more scalable housing type — and investors played a much bigger role, peaking at 44.8% of new housing finance in 2015.

Foreign investors also played a key role, with data from National Australia Bank showing overseas buyers accounted for over 10% of new home purchases for much of the 2010s.

But despite high completion numbers, outcomes were mixed.

“More dwelling completions are not necessarily a mark of success,” Ms Owen notes, pointing to falling homeownership rates, poor capital growth for many investors, and widespread construction defects that rendered some buildings uninhabitable.

In response to past mistakes, today’s new apartments are generally larger, better built, and more suited to owner-occupiers.

Governments have also introduced a range of incentives: NSW has a new “pattern book” of pre-approved designs, sweeping zoning changes, and plans to guarantee presales for certain projects.

Victoria is offering stamp duty concessions, and Queensland has moved to speed up approvals.

Yet new home approvals still remain stubbornly low.

Over the year to June, total dwelling approvals averaged 15,611 — well short of the 20,000 that would be needed each month to meet the 1.2 million homes target.

Ms Owen says the shortfall is due to a combination of high interest rates, lingering affordability concerns and diminished buyer confidence.

“Buyers may also be lacking confidence in new builds following a surge in construction costs between 2021 and 2023,” Ms Owen says.

There was one bright spot: unit approvals surged 34% in June, likely in response to RBA cuts in February and May.

But even this figure remains well below the 13,000-unit monthly peak recorded during the more favourable conditions of the 2010s.

Bottlenecks

Cotality’s Eliza Owen says while governments are focused on increasing approvals, a deeper problem is emerging further down the pipeline.

There are currently 219,000 dwellings under construction and another 30,000 that have been approved but have yet to break ground.

“It’s like turning up the tap on a bath that is already full,” Ms Owen warns.

Compared to the 2010s, the time to complete a dwelling has lengthened considerably, reflecting higher costs, capacity constraints, and declining productivity.

These challenges are preventing the current construction backlog from clearing at the pace seen between 2018 and 2020.

It also raises critical questions about the wisdom of pouring more approvals into a system already under pressure.

“Without increasing the capacity or productivity within the construction sector to take on this additional work, it could even present an upside risk to inflation,” Ms Owen cautions — a concern at a time when lower interest rates are needed to boost housing affordability.

Where to from here?

Cotality’s Head of Research, Eliza Owen, argues governments should prioritise “delivering the pipeline, rather than adding more to it.”

Australia’s dwelling construction productivity has declined by an estimated 12% since the mid-1990s, according to the Productivity Commission.

Fixing that means making homes faster and cheaper to build, without compromising quality.

Solutions could include reducing regulatory barriers, using standardised building templates, and shifting toward smaller, more sustainable housing options.

At the same time, tax reform is back on the agenda.

“Winding back negative gearing and capital gains tax concessions, implementing broad-based land taxes, or including the family home in the pension asset test” are just a few levers Ms Owen says that could be pulled to reduce demand and ease pressure on the construction pipeline.

However, the political appetite for this kind of reform is questionable, even though some of these ideas will be debated at the upcoming National Productivity Summit, where leaders from government, industry and unions will consider ways to reform Australia’s housing market.

The bottom line

Eliza Owen says if governments are serious about hitting the 1.2 million homes target, it’s not enough to fast-track planning and approvals.

They must ensure every approved home actually gets built.

“The conversation is finally shifting beyond approvals and into the real levers of change,” she says.

In other words: more approvals, without reforming how and what is built, may just mean more problems…and importantly, less new homes.

Stay Up to Date

with the Latest Australian Property News, Insights & Education.

.png?width=292&height=292&name=Copy%20Link%20(1).png)

SIGN UP FOR FREE NEWSLETTER

SIGN UP FOR FREE NEWSLETTER

%20Scott%20Kuru%20DPU%20141.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=The%20Senate%20Just%20Exposed%20Australias%20Biggest%20$80%20Billion%20Housing%20Fraud%20(Inquiry%20Launched)%20Scott%20Kuru%20DPU%20141.jpg)

%20Scott%20Kuru%20DPU136.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Aussies%20Just%20Got%20Hit%20With%20Double%20Taxes%20on%20Everything%20(This%20Has%20Gone%20Too%20Far)%20Scott%20Kuru%20DPU136.jpg)

%20Scott%20Kuru%20DPU%20133.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=JUST%20IN%20Something%20Major%20Just%20Flipped%20Australia%E2%80%99s%20Property%20Market%20for%202026%20(No%20One%20Saw%20This%20Coming)%20Scott%20Kuru%20DPU%20133.jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Rental%20Prices%20At%20Record%20Highs%20And%20Vacancy%20Rates%20At%20All%20Time%20Lows%20(New%20Data%20Reveals).jpg)

%20%20DPU%20EP%2014.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Investors%20Shutting%20Out%20First%20Home%20Buyers%20(Investors%20At%20Record%20Highs)%20%20DPU%20EP%2014.jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Darwins%20Property%20Market%20Boom%20or%20Dangerous%20Gamble%20(REVEALED).jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=The%20RBA%E2%80%99s%20Rate%20Cut%20Could%20Explode%20House%20Prices%20(Here%E2%80%99s%20Why).jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Warning%2c%20You%20Might%20Be%20Facing%20Higher%20Taxes%20Soon%20(1).jpg)

.png?width=1920&height=1080&name=Rate%20Drops%20Signal%20BIGGEST%20Property%20Boom%20in%20DECADES%20(1).png)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Labor%20vs%20Liberal%20These%20Housing%20Policies%20Could%20Change%20the%20Property%20Market%20Forever%20(1).jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=QLD%20Slashes%20Stamp%20Duty%20Big%20News%20for%20Investors%20%26%20Home%20Buyers%20(1).jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Trump%20Just%20Slapped%20Tariffs%20%E2%80%93%20Here%E2%80%99s%20What%20It%20Means%20for%20Australia%20(1).jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Federal%20Budget%202025%20More%20Debt%2c%20No%20Housing%20%E2%80%93%20Here%E2%80%99s%20What%20You%20Need%20to%20Know%20(1).jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Australias%20Housing%20Crisis%20is%20about%20to%20get%20MUCH%20Worse%20(New%20Data%20Warns).jpg)

%20(1).jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Australias%20RENTAL%20CRISIS%20Hits%20ROCK%20BOTTOM!%20(2025%20Update)%20(1).jpg)

%20(1).png?width=1920&height=1080&name=Is%20Adelaide%20Still%20a%20Good%20Property%20Investment%20(2025%20UPDATE)%20(1).png)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=RBA%20Shocks%20with%20Rate%20Cuts!%20What%E2%80%99s%20Next%20for%20Property%20Investors%20(1).jpg)

%20(1).jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=I%20Predict%20The%20Feb%20Rate%20Cut%20(My%20Price%20Growth%20Prediction)%20(1).jpg)

.png?width=1920&height=1080&name=Why%20Property%20Prices%20Will%20Rise%20in%202025%20Market%20Predictions%20(1).png)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Why%20Investors%20Are%20Choosing%20Apartments%20Over%20Houses%202%20(1).jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Why%20Rate%20Cuts%20Will%20Trigger%20A%20Property%20Boom%20(1).jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Retire%20On%202Million%20With%20One%20Property%20(Using%20SMSF).jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=4%20Reasons%20Why%20You%20Should%20Invest%20in%20Melbourne%20Now%20(1).jpg)

%20(1).jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Old%20Property%20vs%20New%20Property%20(Facts%20and%20Figures%20Revealed)%20(1).jpg)

%20(1).jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Will%20The%20New%20QLD%20Govt%20Create%20a%20Property%20Boom%20or%20Bust%20(My%20Prediction)%20(1).jpg)

%20Scott%20Kuru%20(1).jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Inflation%20Hits%20Three-Year%20Low%20(Will%20RBA%20Cut%20Rates%20Soon)%20Scott%20Kuru%20(1).jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=How%20to%20Buy%20Investment%20Property%20Through%20SMSF_%20The%20Ultimate%20Guide%20(1).jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Victoria%20Slashes%20Stamp%20Duty%20Melbourne%20Set%20to%20Boom%20Scott%20Kuru%20(1).jpg)

.png?width=1571&height=861&name=Are%20Foreign%20Buyers%20Really%20Driving%20Up%20Australian%20Property%20Prices%20(1).png)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=The%20Single%20Factor%20That%20Predicts%20Property%20Growth%20Regions%20(1).jpg)

%20Scott%20Kuru%20(1).jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=My%20Prediction%20On%20Rates%20%26%20Negative%20Gearing%20(Market%20Crash)%20Scott%20Kuru%20(1).jpg)

-1.png?width=1920&height=1080&name=Major%20Banks%20Cut%20Rates%20Will%20RBA%20Follow%20Suit%20(Sept%20Rate%20Update)-1.png)

%20Scott%20Kuru-1.png?width=1920&height=1080&name=Rate%20Cut%20Coming%20What%20New%20Zealands%20Move%20Means%20for%20Australia%20(Sept%20Prediction)%20Scott%20Kuru-1.png)

%20(1).jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Buy%20when%20the%20interest%20rates%20are%20high!%20(Why%20you%20must%20buy%20now!)%20(1).jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Carms_Revised%20Taxes%20Due%20Aug%209%20YT%20Thumbnail02%20(1).jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Carms_Too%20Little%20Too%20Late%20Aug%207%20YT%20Thumbnail01%20(1).jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Carms_Rate%20Drop%20In%20July%20Jun%2010%20YT%20Thumbnail02%20(1).jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Carms_Own%20a%20Property%20V6%20Jun%205_YT%20Thumbnail%20(1).jpg)

.png?width=1920&height=1080&name=Artboard%201%20(3).png)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=YT%20thumbnail%20%20(1).jpg)