Features > Property News & Insights > In-Depth Analyses

Why the national housing target of 1.2m homes will not be achieved

KEY POINTS

- Oxford Economics expects the RBA to delay rate cuts until mid-2025

- Construction of new homes will take years to ramp up, falling short of targets

- The 1.2 million homes goal by 2029 is unlikely to be met

A major economic forecaster says interest rate cuts are unlikely in Australia until at least the second quarter of next year, while continuing problems in the building industry will mean the supply of new homes will be limited for at least the next 5 years.

The predictions from Oxford Economics Australia have been released ahead of the forecaster’s bi-annual economic outlook and construction conferences in Sydney and Melbourne this week.

Interest rates

The team at Oxford Economics has taken an in-depth look at global and local conditions and trends to come up with a comprehensive set of forecasts that cover everything from whether Australia will meet its carbon reduction targets, to what a Donald Trump victory in the US Presidential election might mean for stock markets.

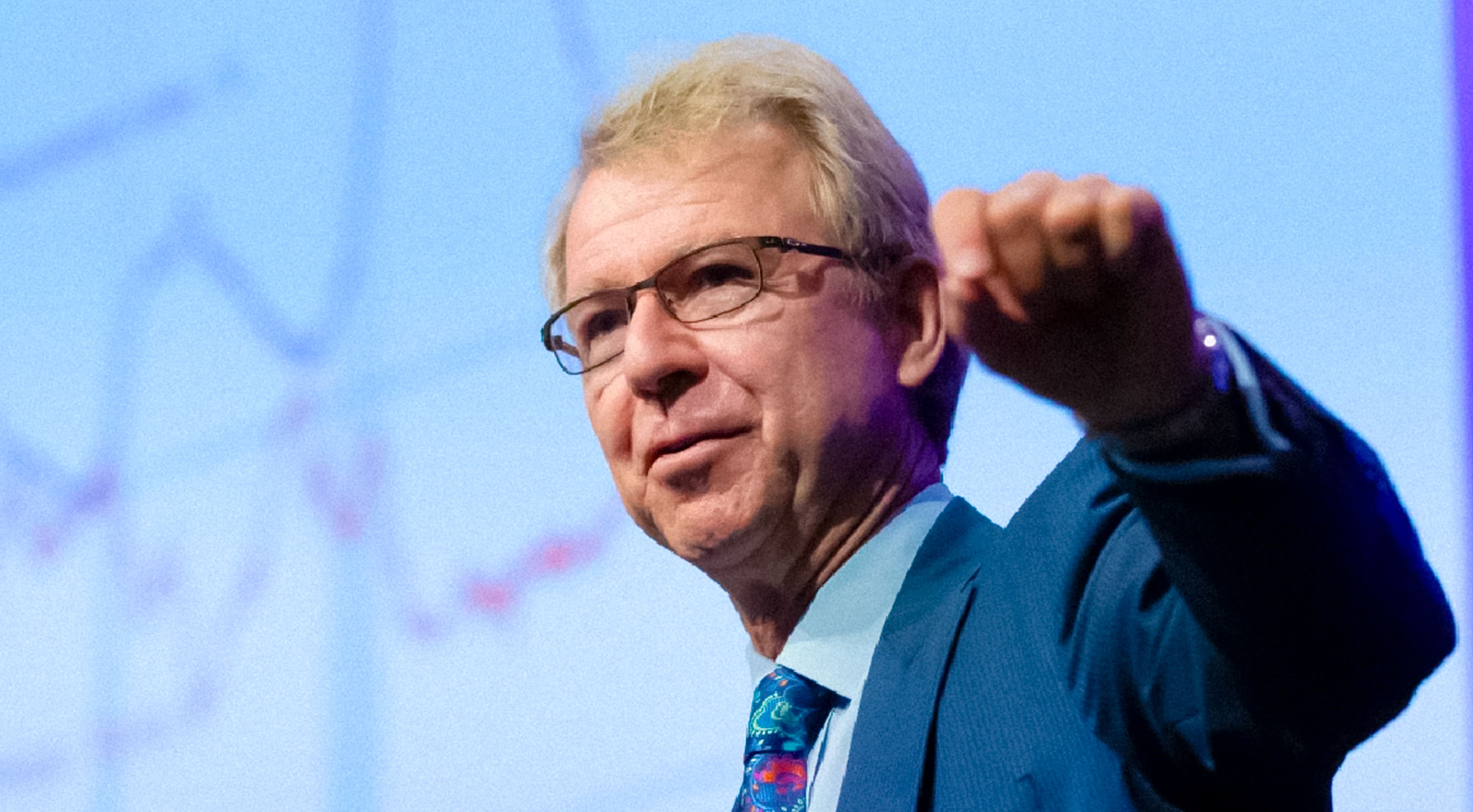

“The Australian economy is set to be buffeted by a diverse set of global, market shifting forces,” says Sean Langcake, Head of Macroeconomic Forecasting for Oxford Economics Australia.

Mr. Langcake expects headline inflation in Australia to be very close to the top of the Reserve Bank of Australia’s (RBA) 2-3% target range by the end of this year, with government energy subsidies providing much of the “disinflation impetus".

However, he believes the central bank will largely ignore the headline data and won’t start cutting the cash rate (currently at a 12 year high of 4.35%) until April or May (there’s no scheduled RBA board meeting in June) of next year.

“Given the RBA’s hawkish rhetoric, we don’t see rate cuts coming until Q2 2025,” he says.

“The labour market has defied a marked slowdown in activity, which is testing the RBA’s very patient approach to bringing inflation back to its target.”

The Assistant RBA Governor Sarah Hunter recently gave a speech where she said the bank was finding the strength of the job market “surprising”, as it is “occurring against a backdrop of slow momentum in the economy.”

Housing

AMP’s Chief Economist Shane Oliver recently estimated that Australia was already between 200,000 and 300,000 homes short before the National Housing Accord formally came into force on the 1st of July this year.

That’s the ambitious agreement between the Federal government, the states and territories, and the housing industry to build 1.2 million homes over the next five years to house a growing population.

To meet that 2029 target (without even worrying about making up the existing housing shortfall) would require the construction of around 240,000 new homes each year, but Oxford’s latest forecasts indicate residential building will only begin to ramp up to anywhere near those levels in 2028-29.

Australian Bureau of Statistics figures indicate just under 172,000 new homes were completed in the 12 months to March 2024.

Oxford Economics says higher construction costs and interest rates continue to drag on housing demand and private investment, while delays and builders going broke have “further suppressed the confidence of developers and home buyers alike”.

“We expect supply to climb in the back half of the decade, reaching 220,000 total dwelling completions in FY29,” says Maree Kilroy, Oxford’s Senior Economist for Construction & Property Forecasting.

“However, industry capacity represents the most significant downside risk to the outlook for new housing.”

“Persistent shortages of skilled trade labour will place a speed limit on the early-to-mid stage recovery,” she says.

“Construction insolvencies are expected to continue to surge over 2024, while issues with utility connections across our major cities may also act as a drag near term.”

Population

Australia already had a substantial housing shortfall, before the crisis was exacerbated by the large numbers of long-term migrants entering Australia when borders reopened after the Covid-19 pandemic.

Net Overseas Migration for the 12-month period to September 2023 was 548,800, the highest yearly intake in Australia's history.

Oxford Economics Australia says it believes migration is slowing, “with recent policy tweaks focused on international student flows expected to see net overseas migration halve from the current boom level to 250,000” by 2025-26.

However, that is still an extremely high population intake at the time of a housing shortage.

The take-out

Oxford Economics’ Maree Kilroy believes that with “strong population growth powering underlying demand, the Australian building sector is primed for a broad upturn once conditions become more supportive.”

The problem is those “supportive” conditions (lower interest rates, less builder insolvencies, a larger supply of construction workers, greater industry and consumer confidence) don’t exist yet, and are unlikely to exist for several years.

That means Australia’s severe housing shortage will continue for the foreseeable future.

Stay Up to Date

with the Latest Australian Property News, Insights & Education.

.png?width=292&height=292&name=Copy%20Link%20(1).png)

SIGN UP FOR FREE NEWSLETTER

SIGN UP FOR FREE NEWSLETTER

%20(1).png)

%20Scott%20Kuru%20DPU%20158.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=JUST%20IN%20Australia%E2%80%99s%20Builder%20Collapse%20Has%20Officially%20Begun%20(Millions%20Will%20Pay%20The%20Price%20in%202026)%20Scott%20Kuru%20DPU%20158.jpg)

%20Scott%20Kuru%20DPU%20157.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=JUST%20IN%20Something%20Major%20Just%20Flipped%20Australia%E2%80%99s%20Property%20Market%20for%202026%20(No%20One%20Has%20Noticed%20Yet)%20Scott%20Kuru%20DPU%20157.jpg)

%20Scott%20Kuru%20DPU%20156.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=BREAKING%20Do%20China%20and%20Japan%20Now%20Own%20Most%20of%20Australia%E2%80%99s%20Property%20Market%20(New%20Data%20Out)%20Scott%20Kuru%20DPU%20156.jpg)

%20Scott%20Kuru%20DPU%20154.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=WARNING%20Australia%E2%80%99s%20Cost%20of%20Living%20Crisis%20Has%20Reached%20a%20Breaking%20Point%20(Millions%20Will%20Be%20Homeless)%20Scott%20Kuru%20DPU%20154.jpg)

%20Scott%20Kuru%20DPU%20153.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Senate%20Inquiry%20Exposes%20Australia%E2%80%99s%20Oil%20Crisis%20Far%20Worse%20Than%20Expected%20($50%20Billion%20Lost)%20Scott%20Kuru%20DPU%20153.jpg)

%20Scott%20Kuru%20DPU%20150.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=BREAKING%20Senate%20Hearing%20Proves%20They%20Deliberately%20Inflated%20House%20Prices%20(This%20Wasnt%20an%20Accident)%20Scott%20Kuru%20DPU%20150.jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=WARNING%20Australia%E2%80%99s%20High%20Debt%20Levels%20Could%20Collapse%20the%20Economy%20-%20Are%20We%20Headed%20for%20Bankruptcy%20Scott%20Kuru%20DPU%20149%20(1).jpg)

%20Scott%20Kuru%20DPU%20148.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Australia%20Is%20on%20the%20Brink%20of%20History%E2%80%99s%20Worst%20Mortgage%20Default%20Crisis%20(Housing%20Crash%20Inevitable)%20Scott%20Kuru%20DPU%20148.jpg)

%20Scott%20Kuru%20DPU%20147.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=RBA%20Warns%20Inflation%20Has%20Pushed%20Australia%20Into%20Household%20Recession%20(Millions%20Face%20Pay%20Cuts%20in%202026)%20Scott%20Kuru%20DPU%20147.jpg)

%20Scott%20Kuru%20DPU%20145.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Senate%20Inquiry%20Forced%20the%20RBA%20to%20Admit%20the%20Housing%20Crisis%20Will%20Never%20Be%20Fixed%20(It%20Was%20All%20a%20Lie)%20Scott%20Kuru%20DPU%20145.jpg)

%20Scott%20Kuru%20DPU%20141.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=The%20Senate%20Just%20Exposed%20Australias%20Biggest%20$80%20Billion%20Housing%20Fraud%20(Inquiry%20Launched)%20Scott%20Kuru%20DPU%20141.jpg)

%20Scott%20Kuru%20DPU136.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Aussies%20Just%20Got%20Hit%20With%20Double%20Taxes%20on%20Everything%20(This%20Has%20Gone%20Too%20Far)%20Scott%20Kuru%20DPU136.jpg)

%20Scott%20Kuru%20DPU%20133.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=JUST%20IN%20Something%20Major%20Just%20Flipped%20Australia%E2%80%99s%20Property%20Market%20for%202026%20(No%20One%20Saw%20This%20Coming)%20Scott%20Kuru%20DPU%20133.jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Rental%20Prices%20At%20Record%20Highs%20And%20Vacancy%20Rates%20At%20All%20Time%20Lows%20(New%20Data%20Reveals).jpg)

%20%20DPU%20EP%2014.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Investors%20Shutting%20Out%20First%20Home%20Buyers%20(Investors%20At%20Record%20Highs)%20%20DPU%20EP%2014.jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Darwins%20Property%20Market%20Boom%20or%20Dangerous%20Gamble%20(REVEALED).jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=The%20RBA%E2%80%99s%20Rate%20Cut%20Could%20Explode%20House%20Prices%20(Here%E2%80%99s%20Why).jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Warning%2c%20You%20Might%20Be%20Facing%20Higher%20Taxes%20Soon%20(1).jpg)

.png?width=1920&height=1080&name=Rate%20Drops%20Signal%20BIGGEST%20Property%20Boom%20in%20DECADES%20(1).png)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Labor%20vs%20Liberal%20These%20Housing%20Policies%20Could%20Change%20the%20Property%20Market%20Forever%20(1).jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=QLD%20Slashes%20Stamp%20Duty%20Big%20News%20for%20Investors%20%26%20Home%20Buyers%20(1).jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Trump%20Just%20Slapped%20Tariffs%20%E2%80%93%20Here%E2%80%99s%20What%20It%20Means%20for%20Australia%20(1).jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Federal%20Budget%202025%20More%20Debt%2c%20No%20Housing%20%E2%80%93%20Here%E2%80%99s%20What%20You%20Need%20to%20Know%20(1).jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Australias%20Housing%20Crisis%20is%20about%20to%20get%20MUCH%20Worse%20(New%20Data%20Warns).jpg)

%20(1).jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Australias%20RENTAL%20CRISIS%20Hits%20ROCK%20BOTTOM!%20(2025%20Update)%20(1).jpg)

%20(1).png?width=1920&height=1080&name=Is%20Adelaide%20Still%20a%20Good%20Property%20Investment%20(2025%20UPDATE)%20(1).png)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=RBA%20Shocks%20with%20Rate%20Cuts!%20What%E2%80%99s%20Next%20for%20Property%20Investors%20(1).jpg)

%20(1).jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=I%20Predict%20The%20Feb%20Rate%20Cut%20(My%20Price%20Growth%20Prediction)%20(1).jpg)

.png?width=1920&height=1080&name=Why%20Property%20Prices%20Will%20Rise%20in%202025%20Market%20Predictions%20(1).png)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Why%20Investors%20Are%20Choosing%20Apartments%20Over%20Houses%202%20(1).jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Why%20Rate%20Cuts%20Will%20Trigger%20A%20Property%20Boom%20(1).jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Retire%20On%202Million%20With%20One%20Property%20(Using%20SMSF).jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=4%20Reasons%20Why%20You%20Should%20Invest%20in%20Melbourne%20Now%20(1).jpg)

%20(1).jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Old%20Property%20vs%20New%20Property%20(Facts%20and%20Figures%20Revealed)%20(1).jpg)

%20(1).jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Will%20The%20New%20QLD%20Govt%20Create%20a%20Property%20Boom%20or%20Bust%20(My%20Prediction)%20(1).jpg)

%20Scott%20Kuru%20(1).jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Inflation%20Hits%20Three-Year%20Low%20(Will%20RBA%20Cut%20Rates%20Soon)%20Scott%20Kuru%20(1).jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=How%20to%20Buy%20Investment%20Property%20Through%20SMSF_%20The%20Ultimate%20Guide%20(1).jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Victoria%20Slashes%20Stamp%20Duty%20Melbourne%20Set%20to%20Boom%20Scott%20Kuru%20(1).jpg)

.png?width=1571&height=861&name=Are%20Foreign%20Buyers%20Really%20Driving%20Up%20Australian%20Property%20Prices%20(1).png)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=The%20Single%20Factor%20That%20Predicts%20Property%20Growth%20Regions%20(1).jpg)

%20Scott%20Kuru%20(1).jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=My%20Prediction%20On%20Rates%20%26%20Negative%20Gearing%20(Market%20Crash)%20Scott%20Kuru%20(1).jpg)

-1.png?width=1920&height=1080&name=Major%20Banks%20Cut%20Rates%20Will%20RBA%20Follow%20Suit%20(Sept%20Rate%20Update)-1.png)

%20Scott%20Kuru-1.png?width=1920&height=1080&name=Rate%20Cut%20Coming%20What%20New%20Zealands%20Move%20Means%20for%20Australia%20(Sept%20Prediction)%20Scott%20Kuru-1.png)

%20(1).jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Buy%20when%20the%20interest%20rates%20are%20high!%20(Why%20you%20must%20buy%20now!)%20(1).jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Carms_Revised%20Taxes%20Due%20Aug%209%20YT%20Thumbnail02%20(1).jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Carms_Too%20Little%20Too%20Late%20Aug%207%20YT%20Thumbnail01%20(1).jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Carms_Rate%20Drop%20In%20July%20Jun%2010%20YT%20Thumbnail02%20(1).jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Carms_Own%20a%20Property%20V6%20Jun%205_YT%20Thumbnail%20(1).jpg)

.png?width=1920&height=1080&name=Artboard%201%20(3).png)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=YT%20thumbnail%20%20(1).jpg)