Features > Property News & Insights > Market updates

Mortgage resilience: Aussies defy rate hikes without falling behind

-1.png)

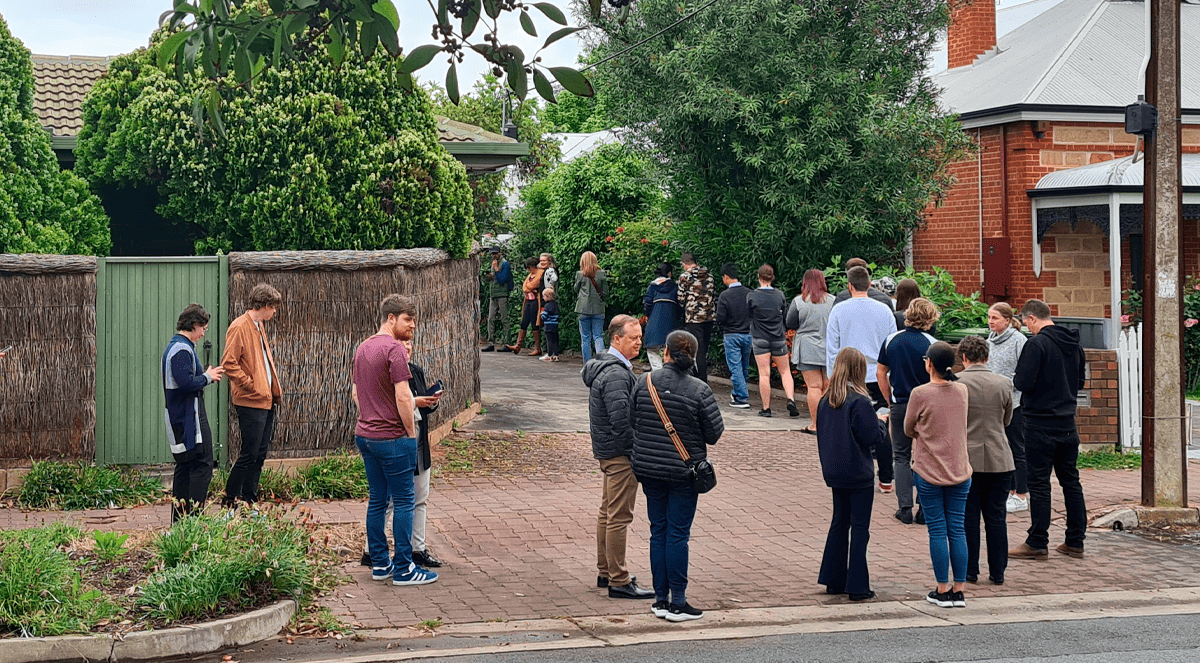

Image by Gaye Gerard/realestate.com.au

KEY POINTS

- Despite high interest rates and cost-of-living pressures, only 1.68% of Australian home loans are in arrears, well below pandemic-era peaks and international benchmarks

- Analysis by Cotality finds that tighter mortgage serviceability rules, low levels of risky lending, and strong employment have helped households stay on top of repayments, even as monthly mortgage costs have surged

- The strength of the Australian residential property market means negative equity also remains extremely rare, with less than 1% of borrowers in a negative equity position

One of the most extraordinary stories to emerge in property over the last three years has been largely overlooked.

It’s the tale of how Australians with a mortgage have been able to withstand a relentless and rapid campaign of interest rate hikes by the Reserve Bank of Australia as the central bank attempted to stamp out an inflation breakout.

That campaign saw official interest rates raised from the emergency pandemic low of 0.1% to 4.35% in just 18 months.

For retail mortgage holders on a variable rate (the majority of borrowers), that meant their rates soared in less than two years from around 2.5% to well over 6%, adding thousands to their monthly interest bills.

Official interest rates were then kept at that decade-high level for more than a year, before the RBA began a slow easing cycle in February 2025.

Yet, despite all this happening in the midst of a cost-of-living crisis, the number of mortgage defaults has been extremely small.

So too has the number of Australians falling behind on their mortgage repayments.

Cotality’s Research Director, Tim Lawless, has been examining why defaults and arrears haven’t been higher in Australia and why they’ve stayed well below international benchmarks.

He’s found a combination of tough lending criteria, a strong jobs market, large savings buffers, very little “negative equity,” and cost-cutting by households in mortgage “stress” has led to this remarkable outcome.

The details

While mortgage arrears have risen from record lows, the portion of borrowers falling behind on their repayments remains well below 2% of all outstanding home loans.

Australian Prudential Regulation Authority data measuring the proportion of borrowers who are overdue on their mortgage repayments edged slightly higher through the March quarter of 2025, to 1.68%.

However, mortgage arrears remain below a high of 1.86% recorded in April, May and June of 2020, when variable retail interest rates were only about 3%.

As Cotality’s Tim Lawless explains, “Mortgage arrears include loans that are 30-89 days overdue as well as those categorised as non-performing.”

“A non-performing loan is one where the borrower is 90 days or more past due on their repayments or where the lender considers the borrower unlikely to pay their credit obligations without recourse from the lender.”

Mr Lawless points out that while highly leveraged borrowers and lower-income households tend to have higher arrears rates, “even in these categories, arrears are generally low and trending lower.”

So why haven’t there been more defaults?

“Several factors help explain how the vast majority of mortgagors have kept on top of their mortgage repayments during a period of elevated interest rates and severe cost-of-living pressures,” Tim Lawless says, “including strong prudential standards, tight labour markets, extremely low levels of negative equity, and accrued liquidity buffers.

“Lending standards have been unquestionably strong throughout the recent cycle, with a consistently low portion of mortgage originations considered ‘risky’.

“The mortgage serviceability buffer, which assesses prospective borrowers on their ability to repay a mortgage at three percentage points above the current mortgage rate, has also played into the resilience of borrowers,” he says.

“Lifting the buffer from 2.5 percentage points to 3.0 percentage points in October 2021 has helped to lower the default risk, even though mortgage rates have risen a lot more than three percentage points from their 2022 lows.”

Although interest rates are now falling, Tim Lawless says there is no sign from APRA that the serviceability buffer will be lowered.

“While tight lending policies have contributed to financial stability and provided protection for borrowers, there is a counter-argument that lending policies may be too tight, reducing access to credit,” he notes.

The ‘double trigger’

Mr Lawless also highlights what the Reserve Bank has referred to as the “double trigger”.

“The RBA has previously theorised that higher mortgage arrears rates would need to be predicated by a ‘double-trigger’ of both an inability to repay the loan and for the loan to be in a negative equity position,” he says.

“So far, most borrowers have retained their ability to pay despite higher debt servicing costs, thanks to persistently tight labour market conditions, while instances of negative equity remain rare across the Australian housing market.”

A borrower with a $750,000 mortgage would have seen their repayments rise by more than $1500 a month on average between April 2022 and November 2023, and then stay at that level until February this year.

“However, most Australians have retained an ability to service their mortgage through gainful employment, with labour markets holding tight,” Mr Lawless says.

“The unemployment rate came in at 4.1% in May and has held around this level or lower since early 2022.

“Similarly, underemployment, which measures workers who want to work more hours, remains close to multi-decade lows.”

The second component of the “double trigger” relates to negative equity in housing markets, or where the value of property is less than the debt owed.

However, with the Australian residential property market recovering strongly after an initial drop in values when interest rates first started being raised, this has not emerged as a major problem.

“The RBA estimated in their most recent Financial Stability Review that less than 1% of households are experiencing a negative equity situation,” Cotality’s Tim Lawless says.

“Given the low portion of homes in negative equity, most borrowers facing financial hardship should be able to sell their property and clear their debt before moving into default.”

Savings buffers and belt-tightening

Mr Lawless says another factor which has helped households deal with suddenly larger mortgage bills is the large savings buffers many Australian households built up during the pandemic.

“Households have been able to draw down on their savings as higher debt servicing costs and cost-of-living pressures eroded balance sheets.”

The Cotality Research Director says that although it's harder to measure, households have also pulled back on non-essential spending, focusing on repaying debt and essential cost-of-living expenses.

Looking forward

“Overall, it’s likely mortgage arrears will trend lower from here as mortgage rates continue to reduce and cost-of-living pressures ease further,” Tim Lawless says.

And he says that with housing values again seeing a broad-based rise, “instances of negative equity are expected to remain a tiny portion of Australian housing stock, providing further resilience to default.”

Tim Lawless’ analysis should be noted by would-be property buyers or investors who are waiting for property prices to fall, and by those who are waiting for a large pool of so-called “distressed listings” - where owners facing the prospect of default are forced into selling their properties at a discounted price.

With tough lending rules, a big pool of savings, a strong labour market, and house prices again on an upward march, these scenarios look increasingly “pie-in-the-sky”.

Stay Up to Date

with the Latest Australian Property News, Insights & Education.

.png?width=292&height=292&name=Copy%20Link%20(1).png)

SIGN UP FOR FREE NEWSLETTER

SIGN UP FOR FREE NEWSLETTER

%20Scott%20Kuru%20DPU%20141.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=The%20Senate%20Just%20Exposed%20Australias%20Biggest%20$80%20Billion%20Housing%20Fraud%20(Inquiry%20Launched)%20Scott%20Kuru%20DPU%20141.jpg)

%20Scott%20Kuru%20DPU136.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Aussies%20Just%20Got%20Hit%20With%20Double%20Taxes%20on%20Everything%20(This%20Has%20Gone%20Too%20Far)%20Scott%20Kuru%20DPU136.jpg)

%20Scott%20Kuru%20DPU%20133.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=JUST%20IN%20Something%20Major%20Just%20Flipped%20Australia%E2%80%99s%20Property%20Market%20for%202026%20(No%20One%20Saw%20This%20Coming)%20Scott%20Kuru%20DPU%20133.jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Rental%20Prices%20At%20Record%20Highs%20And%20Vacancy%20Rates%20At%20All%20Time%20Lows%20(New%20Data%20Reveals).jpg)

%20%20DPU%20EP%2014.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Investors%20Shutting%20Out%20First%20Home%20Buyers%20(Investors%20At%20Record%20Highs)%20%20DPU%20EP%2014.jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Darwins%20Property%20Market%20Boom%20or%20Dangerous%20Gamble%20(REVEALED).jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=The%20RBA%E2%80%99s%20Rate%20Cut%20Could%20Explode%20House%20Prices%20(Here%E2%80%99s%20Why).jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Warning%2c%20You%20Might%20Be%20Facing%20Higher%20Taxes%20Soon%20(1).jpg)

.png?width=1920&height=1080&name=Rate%20Drops%20Signal%20BIGGEST%20Property%20Boom%20in%20DECADES%20(1).png)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Labor%20vs%20Liberal%20These%20Housing%20Policies%20Could%20Change%20the%20Property%20Market%20Forever%20(1).jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=QLD%20Slashes%20Stamp%20Duty%20Big%20News%20for%20Investors%20%26%20Home%20Buyers%20(1).jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Trump%20Just%20Slapped%20Tariffs%20%E2%80%93%20Here%E2%80%99s%20What%20It%20Means%20for%20Australia%20(1).jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Federal%20Budget%202025%20More%20Debt%2c%20No%20Housing%20%E2%80%93%20Here%E2%80%99s%20What%20You%20Need%20to%20Know%20(1).jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Australias%20Housing%20Crisis%20is%20about%20to%20get%20MUCH%20Worse%20(New%20Data%20Warns).jpg)

%20(1).jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Australias%20RENTAL%20CRISIS%20Hits%20ROCK%20BOTTOM!%20(2025%20Update)%20(1).jpg)

%20(1).png?width=1920&height=1080&name=Is%20Adelaide%20Still%20a%20Good%20Property%20Investment%20(2025%20UPDATE)%20(1).png)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=RBA%20Shocks%20with%20Rate%20Cuts!%20What%E2%80%99s%20Next%20for%20Property%20Investors%20(1).jpg)

%20(1).jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=I%20Predict%20The%20Feb%20Rate%20Cut%20(My%20Price%20Growth%20Prediction)%20(1).jpg)

.png?width=1920&height=1080&name=Why%20Property%20Prices%20Will%20Rise%20in%202025%20Market%20Predictions%20(1).png)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Why%20Investors%20Are%20Choosing%20Apartments%20Over%20Houses%202%20(1).jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Why%20Rate%20Cuts%20Will%20Trigger%20A%20Property%20Boom%20(1).jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Retire%20On%202Million%20With%20One%20Property%20(Using%20SMSF).jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=4%20Reasons%20Why%20You%20Should%20Invest%20in%20Melbourne%20Now%20(1).jpg)

%20(1).jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Old%20Property%20vs%20New%20Property%20(Facts%20and%20Figures%20Revealed)%20(1).jpg)

%20(1).jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Will%20The%20New%20QLD%20Govt%20Create%20a%20Property%20Boom%20or%20Bust%20(My%20Prediction)%20(1).jpg)

%20Scott%20Kuru%20(1).jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Inflation%20Hits%20Three-Year%20Low%20(Will%20RBA%20Cut%20Rates%20Soon)%20Scott%20Kuru%20(1).jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=How%20to%20Buy%20Investment%20Property%20Through%20SMSF_%20The%20Ultimate%20Guide%20(1).jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Victoria%20Slashes%20Stamp%20Duty%20Melbourne%20Set%20to%20Boom%20Scott%20Kuru%20(1).jpg)

.png?width=1571&height=861&name=Are%20Foreign%20Buyers%20Really%20Driving%20Up%20Australian%20Property%20Prices%20(1).png)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=The%20Single%20Factor%20That%20Predicts%20Property%20Growth%20Regions%20(1).jpg)

%20Scott%20Kuru%20(1).jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=My%20Prediction%20On%20Rates%20%26%20Negative%20Gearing%20(Market%20Crash)%20Scott%20Kuru%20(1).jpg)

-1.png?width=1920&height=1080&name=Major%20Banks%20Cut%20Rates%20Will%20RBA%20Follow%20Suit%20(Sept%20Rate%20Update)-1.png)

%20Scott%20Kuru-1.png?width=1920&height=1080&name=Rate%20Cut%20Coming%20What%20New%20Zealands%20Move%20Means%20for%20Australia%20(Sept%20Prediction)%20Scott%20Kuru-1.png)

%20(1).jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Buy%20when%20the%20interest%20rates%20are%20high!%20(Why%20you%20must%20buy%20now!)%20(1).jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Carms_Revised%20Taxes%20Due%20Aug%209%20YT%20Thumbnail02%20(1).jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Carms_Too%20Little%20Too%20Late%20Aug%207%20YT%20Thumbnail01%20(1).jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Carms_Rate%20Drop%20In%20July%20Jun%2010%20YT%20Thumbnail02%20(1).jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Carms_Own%20a%20Property%20V6%20Jun%205_YT%20Thumbnail%20(1).jpg)

.png?width=1920&height=1080&name=Artboard%201%20(3).png)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=YT%20thumbnail%20%20(1).jpg)