.jpg)

KEY POINTS

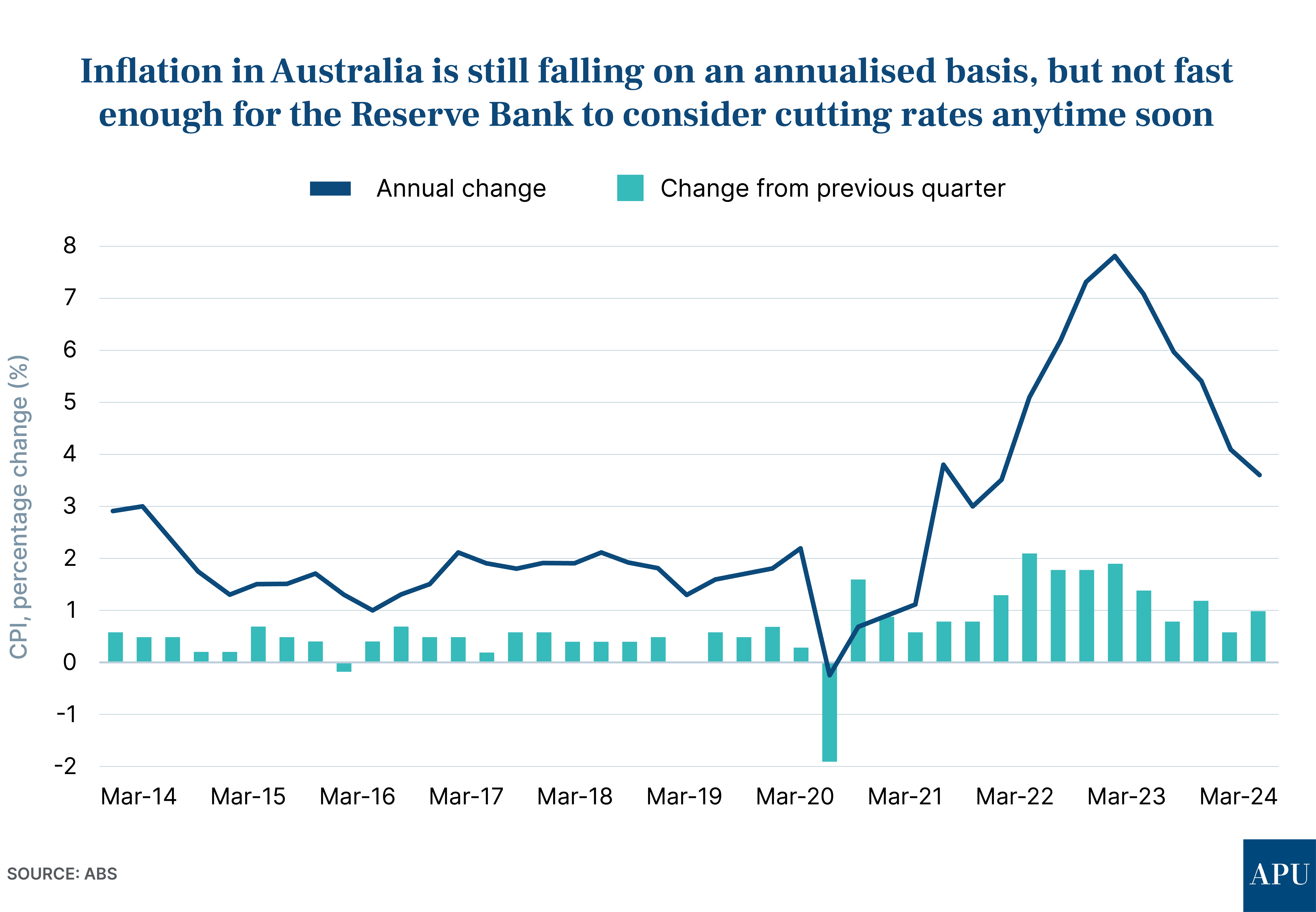

- ABS data shows inflation in the March quarter in Australia was 1%, meaning annual inflation was 3.6% at the end of March

- This was higher than market expectations of 0.8% for the quarter and 3.4% for the year

- The inflation numbers have dashed hopes for an early cut in official interest rates

- As a result of the higher-than-expected numbers, Westpac has pushed back its forecast for the timing of any rate cuts, and ANZ says it is considering what this means for its prediction of a November interest rate cut

Quarterly inflation numbers, released by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), have dashed hopes that the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) will move to cut rates before the final months of this year. A growing number of economists are predicting that any relief for mortgage holders will not come until 2025.

However, the overwhelming majority of analysts believe the prospect of the RBA raising the cash rate again to slow inflation is extremely small.

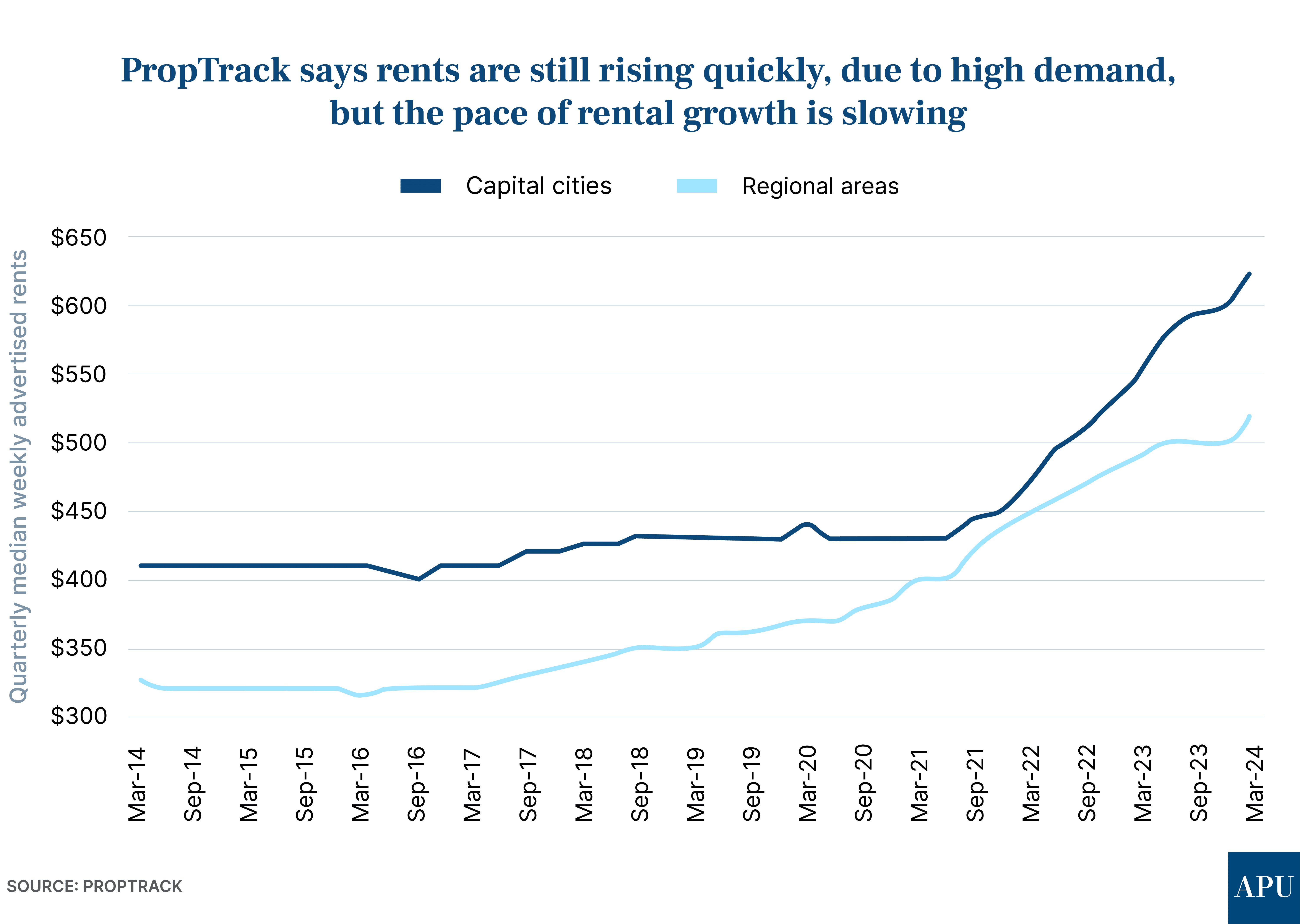

The key to the higher-than-expected inflation number was housing, with new figures from PropTrack showing rent growth remains very strong, although it is starting to slow slightly.

The details

The ABS says the Consumer Price Index, which measures inflation in Australia, rose 1.0% in the quarter ending March 30th, 2024, a figure that came in higher than market expectations of 0.8%.

Looking at it on an annualised basis, over the twelve months to March 2024, Australia’s inflation rate was 3.6%.

The markets had predicted 3.4%.

While that’s significantly less than the 7.8% annual inflation recorded in December 2022, it’s still significantly higher than the RBA’s target band for inflation of 2-3%, which the bank has said must be achieved by the end of 2025.

It’s also worth noting that the RBA’s preferred measure of inflation - the “trimmed mean” - which strips out more volatile components of the inflation measure, also rose by 1.0% over the quarter to be up 4.0% in the year to March (down from 4.2% in the December quarter).

According to the ABS, the most significant price rises this quarter were rents (up 2.1%), secondary education costs (up 6.1%), tertiary education costs (up 6.5%) and medical and hospital services (up 2.3%).

Over the past year, the ABS says rental prices have risen 7.8%, the strongest rise since March 2009.

“Rental price growth continues to reflect low vacancy rates and a tight rental market”, the ABS says.

Separate figures from REA Group’s PropTrack calculate that advertised rents increased by 9.1% or by $50 per week in the year to the end of March.

While that’s extraordinarily rental growth, PropTrack says the pace is moderating, as it’s the first time in two years that rental price growth is below 10%.

Interest rates

Immediately after the inflation numbers were released, the Australian dollar went up half a cent, a jump seen as market traders factored in higher official interest rates in Australia for longer.

“What's quite concerning is that services inflation has actually accelerated on a quarterly basis, and non-tradables (things like water, electricity & gas) inflation is still running too high as well,” says ANZ senior economist Catherine Birch.

“They will certainly be in focus for the RBA.”

“They're reflecting things like…that tightness in the labour market, stronger wages, but also that tightness in the housing market.”

ANZ had been predicting that the Reserve Bank of Australia wouldn’t be in a position to start cutting the official cash rate—which currently stands at a 12-year high of 4.35%—until November this year at the earliest.

Ms Birch says the bank will now review its forecast.

“I think the data today, given that it was a bit stronger than the RBA had pencilled in, particularly on that non-tradables and services side, probably means that the risks have tilted a bit towards a later start to rate cuts,” she says.

However, she thinks the prospect of the RBA raising rates again this cycle is very small.

“You can't write off the possibility of the next move being a hike rather than a cut, but we think it is a pretty low possibility at this stage,” she told ABC News.

Westpac’s chief economist, Luci Ellis, who was an Assistant Governor at the Reserve Bank until late last year, says she’s pushed back her expectations of rate cuts starting in September.

The RBA “will probably continue to be cautious about services inflation and domestic pressures broadly for a few months yet,” she says.

“Given the slower progress on disinflation this quarter and the lower starting point for labour market slack, we now expect the first rate cut to occur after the November (RBA board) meeting, rather than September as previously expected.”

How bad is it really for mortgage holders?

The news that official interest rate cuts will now most likely be pushed back to the end of the year or even 2025, will come as a blow to households struggling with high mortgage repayments, especially those that borrowed large sums when the cash rate was at a historic low of just 0.1%.

Recent data from Fitch Ratings shows mortgage arrears in Australia are at their highest level since May 2020, when arrears spiked due to the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic.

30+ day mortgage arrears rose by 0.1% to 1.21% in the last quarter of 2023.

However, in historical terms, this is actually still quite a low level of mortgage arrears.

A new research paper from Reserve Bank economist Benjamin Ung perhaps explains why.

It finds the retail interest rates paid by outstanding mortgage borrowers increased by around 320 basis points (or 3.2%) between May 2022 and December 2023.

That is actually around 105 basis points (or 1.05%) less than the cumulative increase in the RBA cash rate over the same period.

This “pass-through” of official rate hikes by retail banks has been slower than in other recent times when mortgage rates have gone up sharply.

Benjamin Ung says this is due to the effects of intense mortgage lending competition between banks, financial institutions and brokers, and the unusually high share of outstanding fixed-rate loans.

The problem is that many of those fixed-rate loans—taken out at low rates during the pandemic—have expired or will expire by the end of the year, meaning it’s likely to be a tougher Christmas than last year for many households with a big mortgage.

Stay Up to Date

with the Latest Australian Property News, Insights & Education.

.png?width=292&height=292&name=Copy%20Link%20(1).png)

SIGN UP FOR FREE NEWSLETTER

SIGN UP FOR FREE NEWSLETTER

%20Scott%20Kuru%20DPU%20160.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=FINAL%20WARNING%20Westpac%20Just%20Dropped%20a%20Brutal%20Housing%20Bombshell%20(Australia%20Won%E2%80%99t%20Be%20Ready)%20Scott%20Kuru%20DPU%20160.jpg)

%20Scott%20Kuru%20DPU%20158.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=JUST%20IN%20Australia%E2%80%99s%20Builder%20Collapse%20Has%20Officially%20Begun%20(Millions%20Will%20Pay%20The%20Price%20in%202026)%20Scott%20Kuru%20DPU%20158.jpg)

%20Scott%20Kuru%20DPU%20157.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=JUST%20IN%20Something%20Major%20Just%20Flipped%20Australia%E2%80%99s%20Property%20Market%20for%202026%20(No%20One%20Has%20Noticed%20Yet)%20Scott%20Kuru%20DPU%20157.jpg)

%20Scott%20Kuru%20DPU%20156.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=BREAKING%20Do%20China%20and%20Japan%20Now%20Own%20Most%20of%20Australia%E2%80%99s%20Property%20Market%20(New%20Data%20Out)%20Scott%20Kuru%20DPU%20156.jpg)

%20Scott%20Kuru%20DPU%20154.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=WARNING%20Australia%E2%80%99s%20Cost%20of%20Living%20Crisis%20Has%20Reached%20a%20Breaking%20Point%20(Millions%20Will%20Be%20Homeless)%20Scott%20Kuru%20DPU%20154.jpg)

%20Scott%20Kuru%20DPU%20153.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Senate%20Inquiry%20Exposes%20Australia%E2%80%99s%20Oil%20Crisis%20Far%20Worse%20Than%20Expected%20($50%20Billion%20Lost)%20Scott%20Kuru%20DPU%20153.jpg)

%20Scott%20Kuru%20DPU%20150.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=BREAKING%20Senate%20Hearing%20Proves%20They%20Deliberately%20Inflated%20House%20Prices%20(This%20Wasnt%20an%20Accident)%20Scott%20Kuru%20DPU%20150.jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=WARNING%20Australia%E2%80%99s%20High%20Debt%20Levels%20Could%20Collapse%20the%20Economy%20-%20Are%20We%20Headed%20for%20Bankruptcy%20Scott%20Kuru%20DPU%20149%20(1).jpg)

%20Scott%20Kuru%20DPU%20148.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Australia%20Is%20on%20the%20Brink%20of%20History%E2%80%99s%20Worst%20Mortgage%20Default%20Crisis%20(Housing%20Crash%20Inevitable)%20Scott%20Kuru%20DPU%20148.jpg)

%20Scott%20Kuru%20DPU%20147.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=RBA%20Warns%20Inflation%20Has%20Pushed%20Australia%20Into%20Household%20Recession%20(Millions%20Face%20Pay%20Cuts%20in%202026)%20Scott%20Kuru%20DPU%20147.jpg)

%20Scott%20Kuru%20DPU%20145.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Senate%20Inquiry%20Forced%20the%20RBA%20to%20Admit%20the%20Housing%20Crisis%20Will%20Never%20Be%20Fixed%20(It%20Was%20All%20a%20Lie)%20Scott%20Kuru%20DPU%20145.jpg)

%20Scott%20Kuru%20DPU%20141.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=The%20Senate%20Just%20Exposed%20Australias%20Biggest%20$80%20Billion%20Housing%20Fraud%20(Inquiry%20Launched)%20Scott%20Kuru%20DPU%20141.jpg)

%20Scott%20Kuru%20DPU136.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Aussies%20Just%20Got%20Hit%20With%20Double%20Taxes%20on%20Everything%20(This%20Has%20Gone%20Too%20Far)%20Scott%20Kuru%20DPU136.jpg)

%20Scott%20Kuru%20DPU%20133.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=JUST%20IN%20Something%20Major%20Just%20Flipped%20Australia%E2%80%99s%20Property%20Market%20for%202026%20(No%20One%20Saw%20This%20Coming)%20Scott%20Kuru%20DPU%20133.jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Rental%20Prices%20At%20Record%20Highs%20And%20Vacancy%20Rates%20At%20All%20Time%20Lows%20(New%20Data%20Reveals).jpg)

%20%20DPU%20EP%2014.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Investors%20Shutting%20Out%20First%20Home%20Buyers%20(Investors%20At%20Record%20Highs)%20%20DPU%20EP%2014.jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Darwins%20Property%20Market%20Boom%20or%20Dangerous%20Gamble%20(REVEALED).jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=The%20RBA%E2%80%99s%20Rate%20Cut%20Could%20Explode%20House%20Prices%20(Here%E2%80%99s%20Why).jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Warning%2c%20You%20Might%20Be%20Facing%20Higher%20Taxes%20Soon%20(1).jpg)

.png?width=1920&height=1080&name=Rate%20Drops%20Signal%20BIGGEST%20Property%20Boom%20in%20DECADES%20(1).png)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Labor%20vs%20Liberal%20These%20Housing%20Policies%20Could%20Change%20the%20Property%20Market%20Forever%20(1).jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=QLD%20Slashes%20Stamp%20Duty%20Big%20News%20for%20Investors%20%26%20Home%20Buyers%20(1).jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Trump%20Just%20Slapped%20Tariffs%20%E2%80%93%20Here%E2%80%99s%20What%20It%20Means%20for%20Australia%20(1).jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Federal%20Budget%202025%20More%20Debt%2c%20No%20Housing%20%E2%80%93%20Here%E2%80%99s%20What%20You%20Need%20to%20Know%20(1).jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Australias%20Housing%20Crisis%20is%20about%20to%20get%20MUCH%20Worse%20(New%20Data%20Warns).jpg)

%20(1).jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Australias%20RENTAL%20CRISIS%20Hits%20ROCK%20BOTTOM!%20(2025%20Update)%20(1).jpg)

%20(1).png?width=1920&height=1080&name=Is%20Adelaide%20Still%20a%20Good%20Property%20Investment%20(2025%20UPDATE)%20(1).png)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=RBA%20Shocks%20with%20Rate%20Cuts!%20What%E2%80%99s%20Next%20for%20Property%20Investors%20(1).jpg)

%20(1).jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=I%20Predict%20The%20Feb%20Rate%20Cut%20(My%20Price%20Growth%20Prediction)%20(1).jpg)

.png?width=1920&height=1080&name=Why%20Property%20Prices%20Will%20Rise%20in%202025%20Market%20Predictions%20(1).png)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Why%20Investors%20Are%20Choosing%20Apartments%20Over%20Houses%202%20(1).jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Why%20Rate%20Cuts%20Will%20Trigger%20A%20Property%20Boom%20(1).jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Retire%20On%202Million%20With%20One%20Property%20(Using%20SMSF).jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=4%20Reasons%20Why%20You%20Should%20Invest%20in%20Melbourne%20Now%20(1).jpg)

%20(1).jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Old%20Property%20vs%20New%20Property%20(Facts%20and%20Figures%20Revealed)%20(1).jpg)

%20(1).jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Will%20The%20New%20QLD%20Govt%20Create%20a%20Property%20Boom%20or%20Bust%20(My%20Prediction)%20(1).jpg)

%20Scott%20Kuru%20(1).jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Inflation%20Hits%20Three-Year%20Low%20(Will%20RBA%20Cut%20Rates%20Soon)%20Scott%20Kuru%20(1).jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=How%20to%20Buy%20Investment%20Property%20Through%20SMSF_%20The%20Ultimate%20Guide%20(1).jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Victoria%20Slashes%20Stamp%20Duty%20Melbourne%20Set%20to%20Boom%20Scott%20Kuru%20(1).jpg)

.png?width=1571&height=861&name=Are%20Foreign%20Buyers%20Really%20Driving%20Up%20Australian%20Property%20Prices%20(1).png)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=The%20Single%20Factor%20That%20Predicts%20Property%20Growth%20Regions%20(1).jpg)

%20Scott%20Kuru%20(1).jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=My%20Prediction%20On%20Rates%20%26%20Negative%20Gearing%20(Market%20Crash)%20Scott%20Kuru%20(1).jpg)

-1.png?width=1920&height=1080&name=Major%20Banks%20Cut%20Rates%20Will%20RBA%20Follow%20Suit%20(Sept%20Rate%20Update)-1.png)

%20Scott%20Kuru-1.png?width=1920&height=1080&name=Rate%20Cut%20Coming%20What%20New%20Zealands%20Move%20Means%20for%20Australia%20(Sept%20Prediction)%20Scott%20Kuru-1.png)

%20(1).jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Buy%20when%20the%20interest%20rates%20are%20high!%20(Why%20you%20must%20buy%20now!)%20(1).jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Carms_Revised%20Taxes%20Due%20Aug%209%20YT%20Thumbnail02%20(1).jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Carms_Too%20Little%20Too%20Late%20Aug%207%20YT%20Thumbnail01%20(1).jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Carms_Rate%20Drop%20In%20July%20Jun%2010%20YT%20Thumbnail02%20(1).jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=Carms_Own%20a%20Property%20V6%20Jun%205_YT%20Thumbnail%20(1).jpg)

.png?width=1920&height=1080&name=Artboard%201%20(3).png)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&name=YT%20thumbnail%20%20(1).jpg)